Today is the first day of Indiana's bicentennial year, so Happy Birth Year to the Hoosier State!

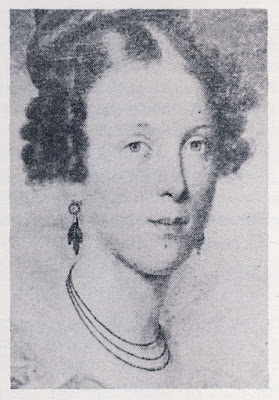

Awhile back, I wrote about Jonathan Jennings (1784-1834), first governor of Indiana. Unfortunately, there isn't any known likeness of his wife, Ann Gilmore Hay Jennings (1792-1825). In fact, there aren't any extant images of Indiana's first four first ladies, at least in the book First Ladies of Indiana and The Governors, 1816-1984 by Margaret Moore Post (1984). The first for whom we have a portrait is Catherine Stull Van Swearingen Noble, shown below. It's the only drawing or painting of a first lady in the book, thus the only work of an artist who was not also a photographer.

Catherine Stull Van Swearingen, called Kitty, was born on August 23, 1801, presumably at her father's plantation at Berryville, Virginia. Her parents were Eli Van Swearingen, a wealthy banker, and Ann (Noble) Van Swearingen. On November 8, 1819, at age eighteen, Kitty married her cousin, Noah Noble (1794-1844), in a Virginia church. Despite the difference in their ages, they had played together as children. Kitty then considered Noah to be "on the bossy side and told him so." (1) After marrying, the two traveled together by horseback to Brookville, Indiana, where Noble had previously been in business. With them were part of Kitty's dowry, what Margaret Moore Post perhaps euphemistically called "black servants." Jonathan Jennings and the first Indiana constitutional convention had ensured that Indiana would be a staunchly free state. The disposition of Kitty's "servants" is unknown, although her husband later provided for former slaves from his father's estate. More on that below.

Noah Noble was made a colonel in the state militia in 1820, the same year in which he was elected sheriff of Franklin County, of which Brookville is the seat of government. In 1823, he was collector of county and state revenue, in 1824 county lister (or assessor). That same year, 1824, Noble was elected to the Indiana House of Representatives. In 1826, he became receiver of public monies in the Indianapolis land office and relocated to the young capital city where he lived the rest of his life.

In the 1820s and perhaps into the 1830s, Noble assembled a large tract of land just east of Indianapolis in what is now the neighborhood of Holy Cross Catholic Church. The boundaries of what was then the Noble farm are College Avenue (then called Noble Avenue) on the west, Arsenal Avenue on the east, St. Clair Avenue on the north, and Washington Street on the south. (2) That figures to about 300 acres in all, an area now occupied by houses and businesses and by about fifteen acres of the grounds of Arsenal Technical High School. There may not be any traces in the area of the Noble family or their presence except for a couple of place names and, if the stories are accurate, an old oak tree, said to have been planted by Kitty Noble in what is now Highland Park. (3)

The Noble house, called Liberty Hall, was a large and very fine house located on Market Street near Pine Street. The ceilings were twelve feet high. Eight fireplaces warmed the bottom floor. A dozen Gordon setters roamed its halls. On the grounds were a vineyard, a peach orchard, an apple orchard, and a sugar grove. The governor and his wife were renowned for their hospitality.

Their entertaining was famous all over the country [wrote the Indianapolis Star in 1964] and invitations to the Noble soirees were greatly sought after. While Kitty was First Lady she entertained at long tables set with rare imported china and silver brought with her as a bride from Virginia. She wore a set of five matching coral cameos presented to "my beloved Kitty" by the Governor with her gowns of damask and velvet. (4)

Kitty Noble bore four children, of which only two, Catherine Mary Noble (1822-1851) and Winston Park Noble (1834-1899), survived to adulthood. "Kitty Noble is said to have spent much time training her daughter and son in duties and manners," wrote Margaret Moore Post, "and the children dressed for dinner each evening." (p. 25) A friend remembered Kitty as "always having a spirit of adventure tempered by a desire for a serious home life and deep rooted Christian faith." (5)

In 1831, Noah Noble's sister, Lavenia Noble Vance (1804-1885), sent former slaves from their father's estate into Noble's care. They were the Magruder family, old Tom, his wife Sarah, and then or later their children, Moses and Louisa. (6) Noble built a cabin for them on his farm in Indianapolis, at the northeast corner of what is now College Avenue and Market Street. A roundabout story leads from Tom Magruder and his cabin to one of the most important novels in American history.

From 1839 to 1847, Henry Ward Beecher (1813-1887) was a minister of the Second Presbyterian Church in Indianapolis. He lived at New Jersey and Market streets, only three blocks west of the Magruder cabin. Beecher was a frequent visitor there and at Liberty Hall. He officiated at the wedding of Catherine Mary Noble to Alexander H. Davidson in 1840. He also spoke at the memorial service of Noah Noble at his death in 1844. In his sermons, he was said to have mentioned Tom Magruder and his deep faith.

Beecher's sister, the writer Harriet Beecher Stowe (1811-1896), visited with her brother during his sojourn in Indianapolis. She is supposed to have met Tom and his family, as well. A strong case can be made that she based the characters from her book Uncle Tom's Cabin (1852), at least in part, on them. A decade after the book, a bestseller, was published, its author met President Abraham Lincoln, who is supposed to have said to her, "So you're the little woman who wrote the book that made this great war!" The story is considered apocryphal. If it were true in any way, we might say that the origins of the Civil War were in Indianapolis, in the area of what is now a nondescript gray brick-and-block building and its parking lot at College and Market. There isn't even a historical plaque to mark the spot where Tom Magruder's cabin once stood.

Noah Noble, a Whig, was elected Indiana's fifth governor in 1831 and served until the end of his second term in 1837. Noble continued in public service after leaving office. His name became associated with disastrous public debt and he returned to private life in 1841. Noah Noble died on February 8, 1844. His wife survived him by thirty years and passed away at age seventy-three on July 12, 1874. Both lie now in Crown Hill Cemetery in Indianapolis. Some of their household furnishings were sent to the Wylie House in Bloomington, Indiana. Noble County, Indiana, is named in his honor.

As for the artist who painted the portrait of Catherine Stull Van Swearingen Noble above, his or her identity is unknown. The image is a scan from Margaret Moore Post's book from 1984. It was probably copied from a photograph that appeared in the Indianapolis Star twenty years before. The caption of that photograph says that the portrait was painted in 1820 and was supposed to have been "an excellent likeness." It does not identify the artist. If the portrait was painted in 1820, it seems unlikely that it was done in Indiana. In a quick search of Pioneer Painters of Indiana by Wilbur D. Peat (1954), I didn't come up with a candidate, as the state was yet so young as to have had few portraitists of sufficient skill. Cincinnati, Kentucky, or even Virginia seem more likely places for its execution. The caption doesn't give the location of the painting, either. It may now be in the collections of Indiana University. I hope that it hasn't been lost, and I hope that someday soon we'll know the name of the artist.

Notes

(1) From "Indiana's Fifth First Lady Grew Up on Virginia Plantation" by Mary Waldon, Indianapolis Star, April 19, 1964, p. 102.

(2) Another source says that the northern boundary of the farm was the present-day New York Street. That would make the Noble property significantly smaller than 300 acres.

(3) St. Clair Avenue was probably named for the St. Clair family, who were connected to the Noble family by the marriage of Lavenia Noble, daughter of Dr. Thomas Noble (1762-1817) and Elizabeth Claire Sedgwick Noble (1764-1830 or 1837) and sister of Noah Noble, to Arthur St. Clair Vance (1801-1849), grandson of Major General Arthur St. Clair II (1737-1818) of Revolutionary War fame. It's worth noting that a character in Uncle Tom's Cabin is named Augustine St. Clare. Some names in the book match up with real-life people connected to the Noble and Magruder families.

Highland Avenue and Highland Park were apparently named for Highland Home, the residence of the Nobles' daughter, Catherine Mary Noble Davidson, and her husband, Alexander H. Davidson. The house was built after the death of Noah Noble. Highland Park, at New York Street and Highland Avenue, now occupies the site of the house, which was torn down in 1898 or shortly thereafter. Alternatively, the home was named after a place already called Highland, situated as it is at an elevation of about 750 feet above sea level and offering a view of the city to the west, which is as much as 45 to 50 feet lower in elevation.

(4) From Waldon in the Indianapolis Star.

(5) Ditto.

(6) The case of Tom Magruder is somewhat confused in that, according to a page on the website of the Indiana Historical Society, a Thomas Megruder, who had a son named Moses, was a slave kept by a James Noble of Dearborn County, Indiana. According to that page, Megruder "remained in the county until Noble's widow died. At that time, Noah Noble, who later became an Indiana governor, gave Megruder his freedom. One of Megruder's sons, Moses, was among those who founded the AME church on Lake Street in Lawrenceburg during the early 1850s." Another document, authored by Allan M. Stranz of the Federal Writers' Project and dated December 29, 1937 (click for a link), would seem to clear up the confusion:

James Noble (1785-1831) was the older brother of Noah Noble, a resident of Lawrenceburg in Dearborn County, a member of the first state constitutional convention, the first U.S. Senator from Indiana, and a prosecutor in the Fall Creek Massacre case. James Noble died in Washington, D.C., in 1831, the same year in which Lavenia Noble Vance sent Tom Magruder and his family to Indianapolis. (The death date of James Noble's wife, Mary Lindsay Noble, is unknown. There seems to be confusion in this case between her and James Noble's mother, Elizabeth Claire Sedgwick Noble, or between James Noble and one of those two women.) The Noble family may have continued to hold the Magruder family as slaves in Kentucky up to that time. According to Allan M. Stranz, "When the widow of Thomas Noble died in 1837 [sic], the [Noble] children agreed among themselves to set the old couple free." The date 1837 may not be correct for the death of Elizabeth Claire Sedgwick Noble. If it was instead 1830, as other sources indicate, then the date for the relocation of Tom and Sarah Magruder to Indianapolis in 1831 fits. Still, it indicates that the Noble family, residents of Indiana, still held slaves as late as 1831. The Magruders were by law the property of Thomas and Elizabeth Noble's daughters: in Dr. Noble's will, the real property had gone to his sons, the personal property, including slaves, to his daughters. Nevertheless, James and Noah Noble, both Whigs and both officeholders in Indiana, a free state, were uncomfortably close to an institution they supposedly abhorred. Today that would make for a scandal of gigantic proportions.

For more on Thomas Megruder, see the website of the Indiana Historical Society, here. For more on Senator James Noble, see: "James Noble" by Nina K. Reid in The Indiana Quarterly Magazine of History, Vol. 9, No. 1 (Mar. 1913), pp. 1-13, here.

|

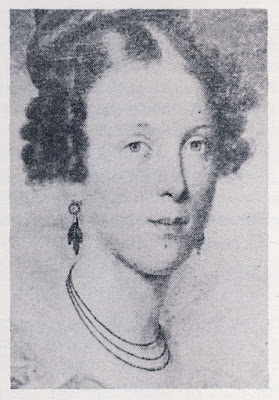

| Noah Noble, a portrait by Jacob Cox from before 1840. Born in 1810 in Philadelphia, Cox arrived in Indianapolis in 1833 and opened a portrait studio in 1835. In all, he painted six portraits of Indiana governors. Cox died in 1892. |

|

I had hoped to find an illustration of Uncle Tom's Cabin done by an Indiana artist--but no luck. Instead, I'll show the cover of Uncle Tom's Cabin for Children, adapted by Helen Ring Robinson (1878-1923), designed by W. M. Rhoads (note the cutout on the cover), and illustrated by at least two artists, one named H.S. Adams, another named Allender. The book was published in Philadelphia by The Penn Publishing Company in 1908.

According to an article in an Indianapolis newspaper of the 1850s, a daguerrotype of the original Magruder cabin was taken before the cabin was "removed." Any daguerrotype has failed to turn up, and the exact meaning of the word removed is unknown--was it torn down, or could someone taking the long view have attempted to save it for posterity? (Source: "Indianapolis Then and Now: Louisa Magruder’s House, 564 N. Highland Avenue" by Joan Hostetler at the website Historic Indianapolis.com, November 21, 2013, accessible by clicking here.) |

Text copyright 2015, 2024 Terence E. Hanley