Thomas Sanford Tousey was born on May 28, 1883, into the wild and wooly West, into a world full of cowboys and Indians, horses and horsemen, and gents who sported big whiskers and carried pistols in their hip pockets. Growing up on a thoroughbred ranch in east Kansas must have been exciting for the future artist, but when Tousey was just eight years old, his family gave up life in the West and moved to Indiana. Throughout his childhood, Tousey returned to his great-grandfather’s ranch near the Potawatami Indian Reservation, to relive the Western way of life he had left behind. He later recounted his experiences in his first children’s book, Cowboy Tommy (1932).

Sanford Tousey (as he came to call himself) graduated from high school in Anderson, Indiana, in 1902. For two years prior, he had earned seven dollars and fifty cents per week drawing daily chalk-plate cartoons for the Anderson Morning Herald. Most of that income went towards schooling at the Art Institute of Chicago under J.C. Leyendecker (1874-1951) and Frederic William Goudy (1865-1941). After that, Tousey went further east, to Wilmington, Delaware, for studies under Howard Pyle (1853-1911), and to the Art Students League in New York. He finished art school in Paris and before long settled into a career as a freelance illustrator and cartoonist in New York. For the next twenty years or so, he made sales to leading popular magazines, including Ballyhoo, Collier’s, Harper’s, Judge, Liberty, Life, Puck, The Saturday Evening Post, and Scribner’s.

During the early 1930s, Tousey gave up freelancing and turned to writing and illustrating children’s books. Over forty titles followed the publication of Cowboy Tommy in 1932, most involving cowboys, Indians, horses, and the Old West. Tousey became one of the bestselling children’s book authors of his day. In addition to authoring and illustrating a series of biographies of famed westerners such as Kit Carson, Buffalo Bill, and Jim Bridger, Tousey illustrated books by others, including Boy on Horseback (1935) by Lincoln Steffens.

Tousey retired in the mid-1950s and died on June 28, 1961, at his home in Monroe, New York. His papers are at the University of Kansas.

Books by Sanford Tousey and Illustrated by Sanford Tousey

Cowboy Tommy: The Story of a Boy's Adventures on a Ranch (1932)

Cowboy Tommy's Roundup (1934)

Boy on Horseback by Lincoln Steffens (1935)

Cowboy Jimmy (1935)

Steamboat Billy (1935)

On the Golden Trail (1936)

Chinky, the Banker Pony (1937)

Jerry and the Pony Express (1937)

Whistling Bill by Florence Romaine (1937)

Chinky Joins the Circus (1938)

Daniel Boone (1939)

The Shining Mountains by Lulita Crawford Pritchett (1939)

Indians of the Plains (1940)

Stagecoach Sam (1940)

Bob and the Railroad (1941)

Ned and the Rustlers (1941, 1945)

The Northwest Mounted Police (1941)

Val Rides the Oregon Trail (1941)

Airplane Andy (1942)

Cowboys of America (1942)

Cowboys of America (1942)

Old Blue, the Cow Pony (1942, 1945)

Pack Jack Trail by Addison Talbott (1942)

Dick and the Canal Boat (1943)

Little Bear's Pinto Pony (1943)

Fred and Brown Beaver Ride the River (1944)

Trouble in the Gulch (1944)

Lumberjack Bill (1946)

Tinker Tim (1946)

Treasure Cave (1946)

Bill and the Circus (1947)

Jack Finds Gold (1947)

Davy Crockett, Hero of the Alamo (1948)

Indians and Cowboys (1948)

Kit Carson, American Scout (1949)

Toby Has a Dog by May Justus (1949)

Horseman Hal (1950)

A Pony for the Boys (1950)

Bill Clark, American Explorer (1951)

The Twin Calves (1951)

White Prince, the Arabian Horse (1951)

Cub Scout (1952)

Jim Bridger, American Frontiersman (1952)

Wild Bill Hickok, Frontier Marshal (1952)

John C. Fremont, Western Pathfinder (date unknown)

|

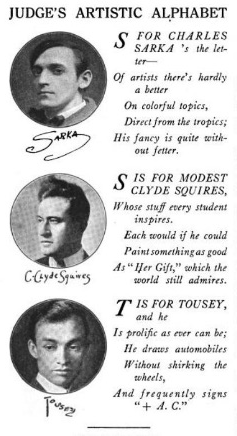

| Revision (March 31, 2021): A photograph of Sanford Tousey, the first I have ever seen. This is from Judge, August 25, 1917. Thanks to Alex Jay for providing the link. |

Revised and updated on July 25, 2020.

Text copyright 2010, 2024 Terence E. Hanley