On the evening of December 4, 1903, Howard Pyle spoke in front of the Irvington Athenæum, a literary and cultural club formed a few years earlier by members of the faculty at Butler University. It was Pyle's first visit to Indiana, but he would not have come as an unknown to a state then renowned for its native and resident artists, including William Merritt Chase (1849-1916), T.C. Steele (1847-1926), William Forsyth (1854-1935), Richard Buckner Gruelle (1851-1914), Otto Stark (1859-1926), and J. Ottis Adams (1851-1927). Some of these men may even have been in the audience on that December evening of long ago. What they heard may have sounded something like a manifesto, a call to the American artist to draw and paint pictures of his or her own time and place, to distinguish himself by placing his art first before the editor of the popular magazine, then before the vast reading public. This would be an art for the common man, made possible by rapid and radical advances in technology, also by a democratic way of life in which art would be available to all and would reflect the experiences of all. It's no coincidence that Pyle would use in his talk a comparison to the development of the steam engine, for with the invention of the steam engine and the popular, pictorial magazine--and by extension all of the other institutions and innovations of liberal democracy--a new age was upon the earth. (1) And by the turn of the nineteenth century, the United States was the leading nation of that new age. Here, then, is the text of an article telling about Howard Pyle's visit in Indiana, from the Indianapolis News, December 5, 1903, page 7:

HOWARD PYLE SPEAKS ON ART OF THE AGE

NOTED ILLUSTRATOR BEFORE IRVINGTON ATHENAEUM.

THE REALLY AMERICAN ART

Howard Pyle, the noted author, artist and illustrator, lectured last night before the Athenæum Club, of Irvington, on "The Art of the Age." He was accompanied by his wife, and an informal reception followed the lecture. He was introduced to the audience by H.U. Brown, (2) who referred to his as coming from the State of Delaware, and said that this was Mr. Pyle’s first visit to Indiana.

Mr. Pyle said: "I must confess that I do come from the effete East, but I hope you will not hold that against me. Many of you here have come from the East, and you may remember that there are glass houses in the West as well as in the East."

He defined art as representing in imagery and picture that for which the age stands in which that art is created. The pictures of the past that have lived have been those that truly represented the age in which they were produced. They might be faulty in drawing or in color, but they were necessarily true in technique. Botticelli’s pictures, he said, represent the childlike enthusiasm of the people of his day as in a later day the creations Michaelangelo [sic] and those of the great Flemish and Spanish painters represent the enormous robustness of an age that was nearing completion.

"So we," he argued, "should hand down to those who follow us the living imagery of what this age stands for. A work of art is a mental image made possible by means of certain technical methods. Everything created by the hand of man must first exist in his mind.

Must Live in Our Own Age

"We can not live to-day in the nineteenth, the eighteenth or the seventeenth century, nor in any century but our own. That which possesses life and power must arise from a living vital mind; otherwise it can not have life. This age is separated from those that are gone by something radical and vital. In the past men lived in a world of effect. To-day we live in a world of causes. The difference between these is the difference between something and nothing. Let us take the creation of the steam engine, the first conception of a young lad observing the kettle boiling over the fire. He sees the steam raise the lid. How was James Watt different from those who had gone before? Millions had seen that same phenomena [sic] of the kettle. In that one moment of observation Watt had stepped from one age into another. At that moment of observation we passed into a new age, the teeming energy of today. * * *

"Do we keep pace in other forms of art with this marvelous phenomenon brought about by the discovery of the power of steam? Do we paint the living things we see to-day about us? Do we paint the pictures that unite man to man, or do we imitate the painters who have gone, who belong to an age that is past? Have we as Americans fulfilled the possibilities of our art?

"We are the possessors of the greatest glories any nation in the world can call its own. We are the inheritors of all the ages. Does our art represent the age in which we live? I think not. We have the greatest sculptors of the world today. Possibly the greatest portrait painters are Americans. It is likely the landscape artists of this country are the peers of those of any other country, but have we created an art that stands for the age? Have our artists in their studios poured forth upon their canvases the life that belongs to this age? I think not.

Wonderful Possibilities

"I think, instead, there is a vast pottering after effects—an effort to produce effects in reds and greens and blues. Look at the wonderful possibilities that lie within our country to create the greatest pictures that could exist in the world. Is there nothing in all our redundant [sic] life that a man must seek the galleries of Europe and learn his mechanism in the schools of Paris?

"The one American art that exists to-day is the art of the illustrator. The illustrator creates that which is American. He is compelled to do so. He has the severest critic in the world—the editor of the magazine, who must consider that which the million people desire to have pictured for them. If there is a failure to do this the magazine will prove a failure. The magazine artist must represent that which is about him.

"So, in the magazine are to be seen all the phases of American life as they stand nowhere else. And from this is to arise the art that is to be handed down to the future. When we begin to paint pictures that are representatIve of American life, all we ask is your support and encouragement. Then other rewards will come fast enough."

Now known as the father of illustration in America, Howard Pyle (1853-1911) started his own school of illustration in his native city of Wilmington, Delaware, in 1900. His most famous student was undoubtedly N.C. Wyeth (1882-1945), but others at his Brandywine School included Hoosier illustrators Gayle Porter Hoskins (1887-1962) of Brazil, Herbert Moore (1881-1943) of Indianapolis, and Olive Rush (1866-1973) of Fairmount. Another student, Frank Schoonover (1877-1972), taught at the Herron School of Art in Indianapolis in the late 1920s or early 1930s.

It is ironic in view of Howard Pyle's words before the Irvington Athenæum that he died and was interred not in the New World but in the Old. He went to Italy in June 1910 for his health and to study the murals in that country. He fell ill and contemplated a return stateside. Instead, Pyle died in Florence on November 9, 1911. A Quaker, he was interred at the Cimitero degli Inglesi, or English Cemetery, a burial ground for Protestants and other non-Roman Catholics. I have been to his grave. It is a simple niche in a columbarium or mausoleum, located towards the rear of the cemetery. The face of the niche, perhaps about the same dimensions as an old-fashioned magazine cover turned sideways, possibly a little larger, is marked only with his name. (I don't think even his dates are on the marker, but I can't be sure. This was several years ago, and we were there at closing hours in late fall, too dark for picture-taking.) If nothing else, the marker on his grave should read: "Father of Illustration in America."

Notes

(1) By Howard Pyle's reference to the invention of the steam engine, I am reminded of Henry Adams' dynamo as a symbol of a changing age, from The Education of Henry Adams (1918).

(2) H.U. Brown was Hilton U. Brown (1859-1958), a graduate of Butler College (later Butler University); reporter, editor, general manager, and vice-president for and of the Indianapolis News; and president of the board of directors of Butler University. When we were kids, our local branch of the Indianapolis Public Library was named for him. I remember seeing his daughter, the author Jean Brown Wagoner (1896-1996), at the Brown Branch, at our school, or maybe somewhere else. My classmate Mary Wagoner is her granddaughter. If I have my geography right, Hilton U. Brown lived across Emerson Avenue from the artist and teacher William Forsyth. I believe his property in Irvington, on the east side of Indianapolis, became part of the grounds of Thomas Carr Howe High School. Now, in our very democratic age, the former site of his grand home is occupied by a gas station.

Original text copyright 2018, 2024 Terence E. Hanley

* * *

Now known as the father of illustration in America, Howard Pyle (1853-1911) started his own school of illustration in his native city of Wilmington, Delaware, in 1900. His most famous student was undoubtedly N.C. Wyeth (1882-1945), but others at his Brandywine School included Hoosier illustrators Gayle Porter Hoskins (1887-1962) of Brazil, Herbert Moore (1881-1943) of Indianapolis, and Olive Rush (1866-1973) of Fairmount. Another student, Frank Schoonover (1877-1972), taught at the Herron School of Art in Indianapolis in the late 1920s or early 1930s.

* * *

It is ironic in view of Howard Pyle's words before the Irvington Athenæum that he died and was interred not in the New World but in the Old. He went to Italy in June 1910 for his health and to study the murals in that country. He fell ill and contemplated a return stateside. Instead, Pyle died in Florence on November 9, 1911. A Quaker, he was interred at the Cimitero degli Inglesi, or English Cemetery, a burial ground for Protestants and other non-Roman Catholics. I have been to his grave. It is a simple niche in a columbarium or mausoleum, located towards the rear of the cemetery. The face of the niche, perhaps about the same dimensions as an old-fashioned magazine cover turned sideways, possibly a little larger, is marked only with his name. (I don't think even his dates are on the marker, but I can't be sure. This was several years ago, and we were there at closing hours in late fall, too dark for picture-taking.) If nothing else, the marker on his grave should read: "Father of Illustration in America."

Notes

(1) By Howard Pyle's reference to the invention of the steam engine, I am reminded of Henry Adams' dynamo as a symbol of a changing age, from The Education of Henry Adams (1918).

(2) H.U. Brown was Hilton U. Brown (1859-1958), a graduate of Butler College (later Butler University); reporter, editor, general manager, and vice-president for and of the Indianapolis News; and president of the board of directors of Butler University. When we were kids, our local branch of the Indianapolis Public Library was named for him. I remember seeing his daughter, the author Jean Brown Wagoner (1896-1996), at the Brown Branch, at our school, or maybe somewhere else. My classmate Mary Wagoner is her granddaughter. If I have my geography right, Hilton U. Brown lived across Emerson Avenue from the artist and teacher William Forsyth. I believe his property in Irvington, on the east side of Indianapolis, became part of the grounds of Thomas Carr Howe High School. Now, in our very democratic age, the former site of his grand home is occupied by a gas station.

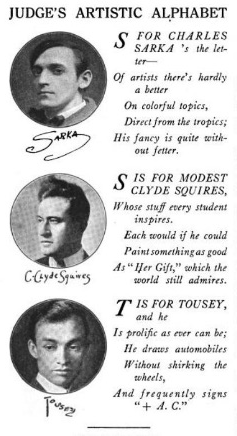

Images from Howard Pyle and His Hoosier Students

|

| The Mermaid, by Howard Pyle, 1910. |

|

| A work by Gayle Porter Hoskins, date unknown. |

|

An illustration by Herbert Moore from The Men Who Founded America (1909).

|

|

| Finally, two covers for Woman's Home Companion by Olive Rush, the December issues of two successive years, 1908 and 1909. |

Original text copyright 2018, 2024 Terence E. Hanley